We begin at the end of the harvest, over a cup of tea around the kitchen table in a farmhouse (built 1604) that has been home to this family for multiple generations. Mark and Leslie Andrews are the 5th generation (12th if you ask Mark’s cousin) of their family cultivating hops, on a farm that has been producing them for at least 350 years.

Often referred to as a cash crop due to the high potential value of the plant, it has been used in brewing since the 9th century. The first documented hop cultivation was in 736, in the Hallertau region of present-day Germany, although the first mention of the use of hops in brewing in that country was 1079 they were clearly being used for something (Charlemagne's father bequeathed the Cloister of Saint-Denis a garden of hops in his will in 768).

Prior to this, brewers used a "gruit", composed of a wide variety of bitter herbs and flowers, including marigold, horehound, burdock, dandelion, ivy, and heather. We have a change in tax law to thank for the wide-scale adoption of hops.

Hopped beer first appeared in the UK as an import from Holland in 1400 but did not catch on as quickly as you might have thought. Condemned as late as 1519 as a "wicked and pernicious weed”, some areas (Norwich we’re looking at you here) went so far as banning the use of the plant in the brewing of ale!

We eventually caught on and caught up, 1752 saw more than 500 tons of English hops imported through Dublin alone. 270 years later, the entire UK crop is now exceeded by single farms in the United States.

But back to farming… What generally goes unsaid is that hops are a delicate plant requiring near perfect conditions in a narrow bandwidth of climate. Oddly similar to potatoes, hops grow best between the 30th and 52nd latitude (Lands End is at 50° and John O’Groats is 58°). In 2022, the high heat levels through June and July, and low rainfall levels have not allowed the hops to grow out properly resulting in a low yield, an early harvest, and our sprint up to Herefordshire to catch the end of it.

From the same family as hemp, cannabis and hackberries (you’ll know when you see them), hops grow to 25ft tall, and are characterised by dark green leaves, papery catkins (female flowers we call hops), and pungent odour.

Springtime in Kent , Herefordshire, and Worcestershire you might be forgiven for questioning the fields of short telephone poles laced together with string. Each variety has its own spacing and growing angle. Planted in rows it’s all about the right amount of sun for the right species, in the right soil, with water at the right time, and the right temperature.

While many brewers stick to the more common varieties like Cascade and Citra, the Andrew’s work with Charles Faram to build a varied portfolio, who carry over 160 varieties from all over the world. With a similar reaction Marmite’s legendary 'You Either Love It Or Hate It' the smell of a hop field ready for picking is an experience in of itself (we’re all big fans as you can imagine), with aromas ranging from black pepper to Lychee.

Here, hops are still harvested by hand, we have not adopted the industrial scale of the US, cultivating hops like a fine wine instead. The bines brought down and into the hopper by a team of 5, their gait is one of years working together, they leave the field ready to reset for the next season.

The full hopper is swiftly returned to the farm buildings, hops are at their best when freshest and perish quickly. The base of the cut bines is fed into a giant track, reminiscent of those in a dry cleaner, and shuttled into the rafters to be separated.

The full hopper is swiftly returned to the farm buildings, hops are at their best when freshest and perish quickly. The base of the cut bines is fed into a giant track, reminiscent of those in a dry cleaner, and shuttled into the rafters to be separated.

Some elements of the machinery here are over 70 years old, purchased by Mark’s grandfather when another local farm closed down. Parts are scavenged from the still older machines they replaced to keep these ones running when something cannot be quickly made, the UK manufacturers having long since gone out of business.

Some elements of the machinery here are over 70 years old, purchased by Mark’s grandfather when another local farm closed down. Parts are scavenged from the still older machines they replaced to keep these ones running when something cannot be quickly made, the UK manufacturers having long since gone out of business.

First stripped from their bines, the hops are then separated from stalks and leaves, and dropped into a kiln for drying. The drying process preserves the hops, dropping them from 80% moisture to 8%, and brings out the depth of their characteristics. The oils and esters in the core of each hop come alive in notes of citrus, spices, herbs, cut grass, pine, florals, resin and fruits.

First stripped from their bines, the hops are then separated from stalks and leaves, and dropped into a kiln for drying. The drying process preserves the hops, dropping them from 80% moisture to 8%, and brings out the depth of their characteristics. The oils and esters in the core of each hop come alive in notes of citrus, spices, herbs, cut grass, pine, florals, resin and fruits.

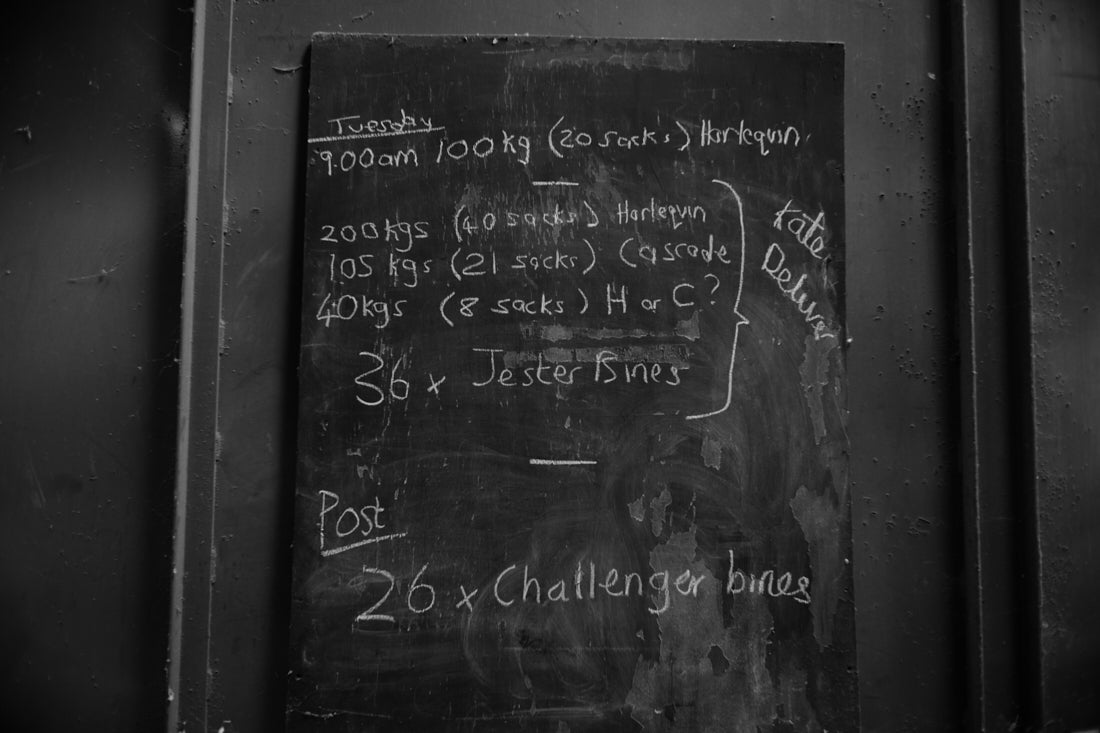

Today, Harlequin is coming in, with it’s bouquet of passionfruit, peach, and pineapple soaking the atmosphere. They are laid down in layers in the kilns, hot air moving through them and carefully watched.

Today, Harlequin is coming in, with it’s bouquet of passionfruit, peach, and pineapple soaking the atmosphere. They are laid down in layers in the kilns, hot air moving through them and carefully watched.

From the kilns the hops are bailed, tested, and ready to move on. The Charles Faram facilities are their next destination and one we will follow later.

If we have inspired you, the farm has the most wonderful guest accommodation, complete with the charming bray-bours Herby and Teddy (they’re in the photo below).

If we have inspired you, the farm has the most wonderful guest accommodation, complete with the charming bray-bours Herby and Teddy (they’re in the photo below).

🍻Cheers! 🍻

About Nirvana Brewery:

We are the UK’s only No/Low alcohol dedicated brewery, one of only 16 Soil Association certified Organic breweries and the only one in London.

We believe that outstanding beer doesn’t need alcohol, that award winning flavour is not tied to abv, and that drinking with friends doesn’t have to mean a slow start the next day.

Brewing since 2016, our beers contain no animal products, less alcohol than orange juice and are between 33 and 66 calories per bottle.